Grain Evolution in a T-Junction by Tinka Gammel

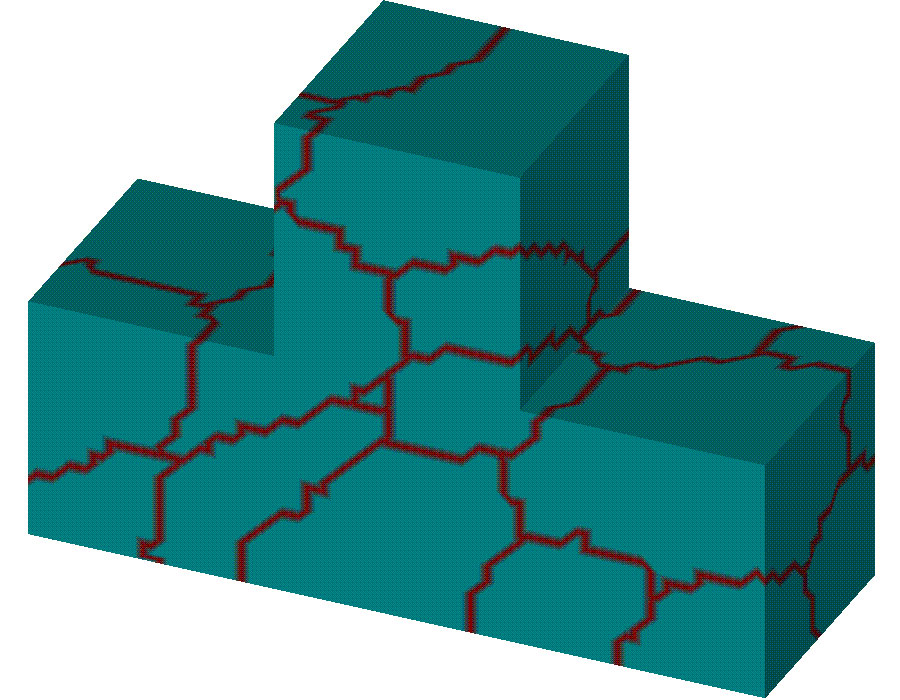

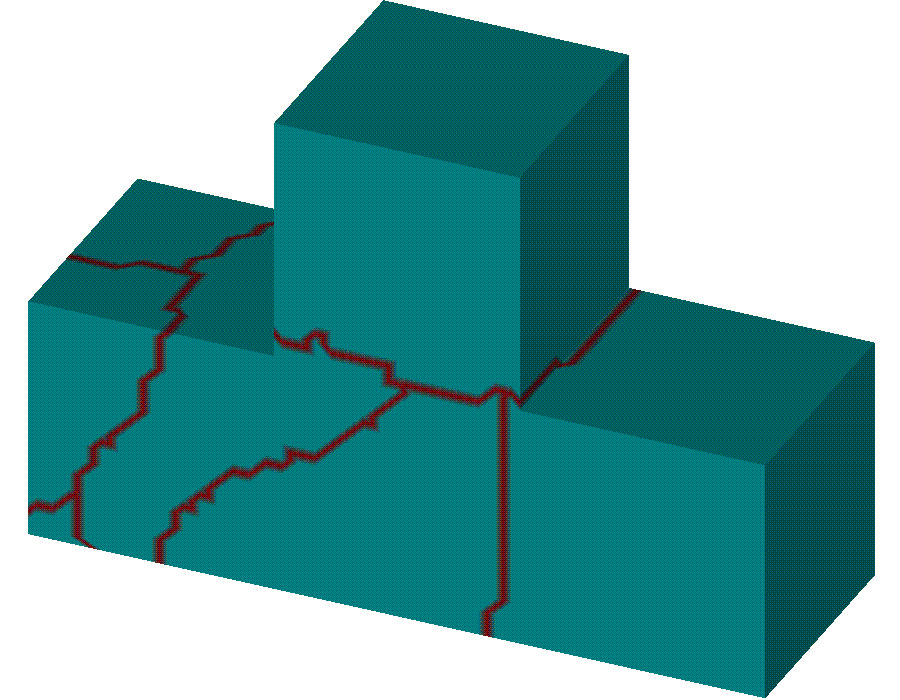

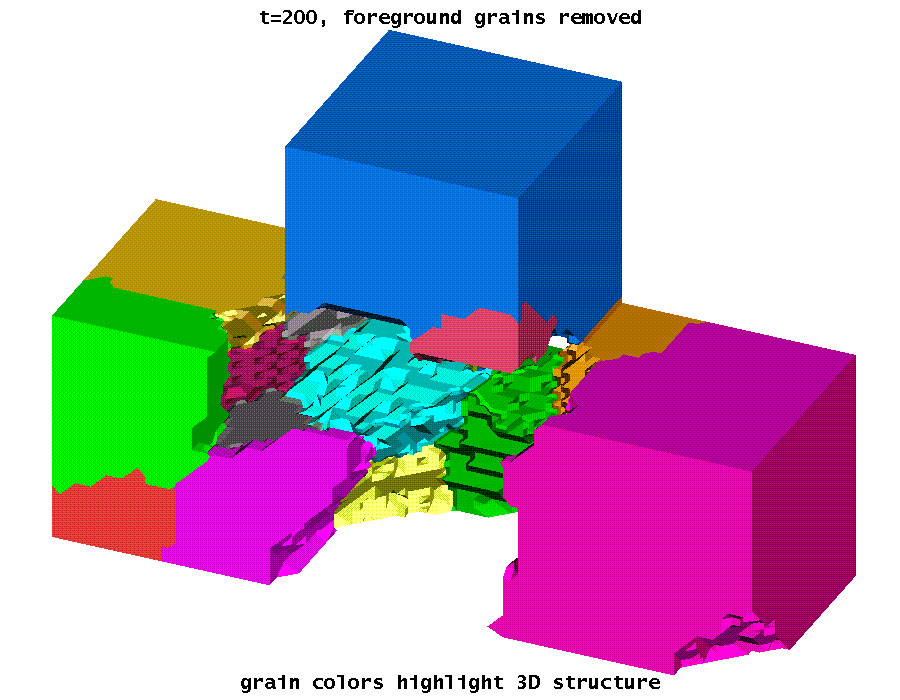

Grain structure of a T-junction obtained via Monte Carlo evolution of a discrete effective classical spin (Potts) model on the nodes of the unstructured tetrahedral grid generated by the LANL LaGriT code for the bounding geometry (taking advantage of LaGriT’s ability to efficiently create and manipulate grids for complex multimaterial geometries, and for compatibility with our finite element calculations). The time unit is Monte Carlo sweeps through the lattice. The node-based Potts model needs fewer neighbors to avoid stagnation and also avoids grain boundaries at topology-defining nodes, which is numerically convenient for using this result as an initial condition for a finite element continuum calculation. The Potts model is known to be the discrete analog of curvature driven grain boundary motion: the irregularities in the grain boundaries reflect the discreteness. Note the T-junction pins a grain boundary, preventing annealing into a single grain.

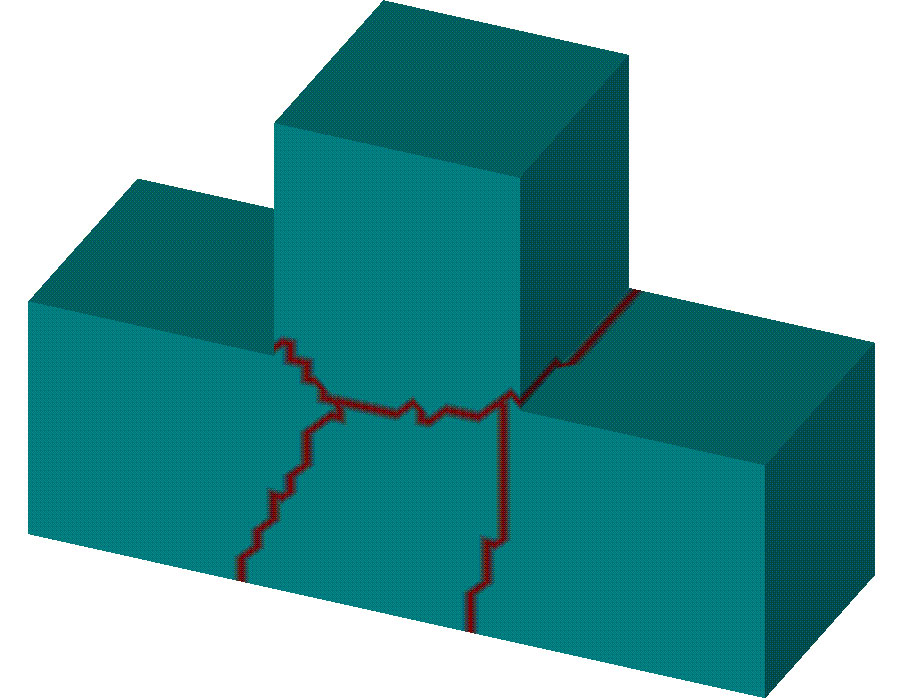

However, the result of the Potts evolution on the unstructured grid is artificially rough, even at fairly high node density, as seen in this close-up of the t=200 microstructure. Fewer nodes results in a rougher structure, and more nodes becomes computationally expensive.

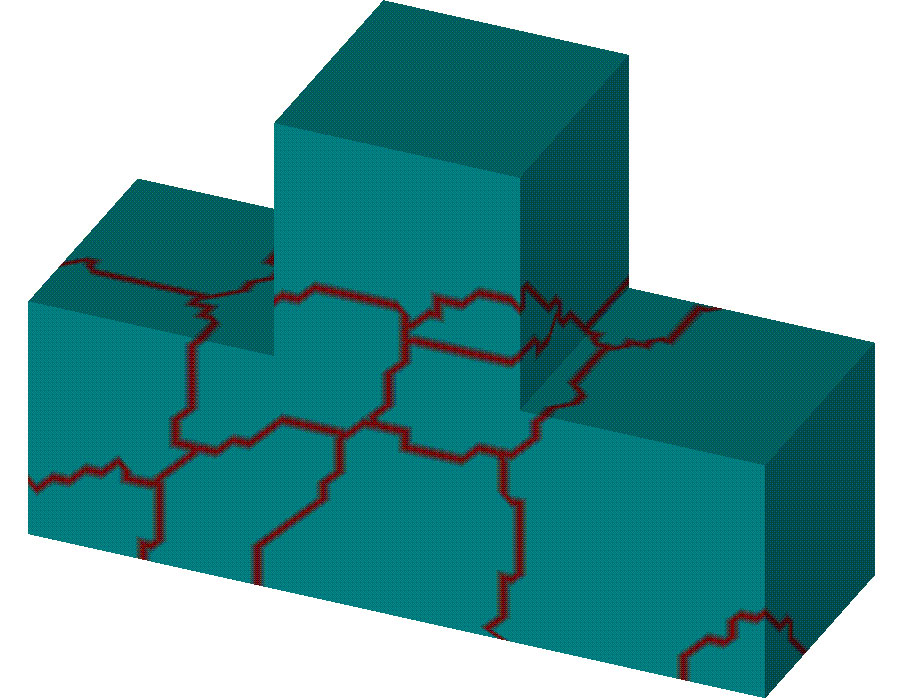

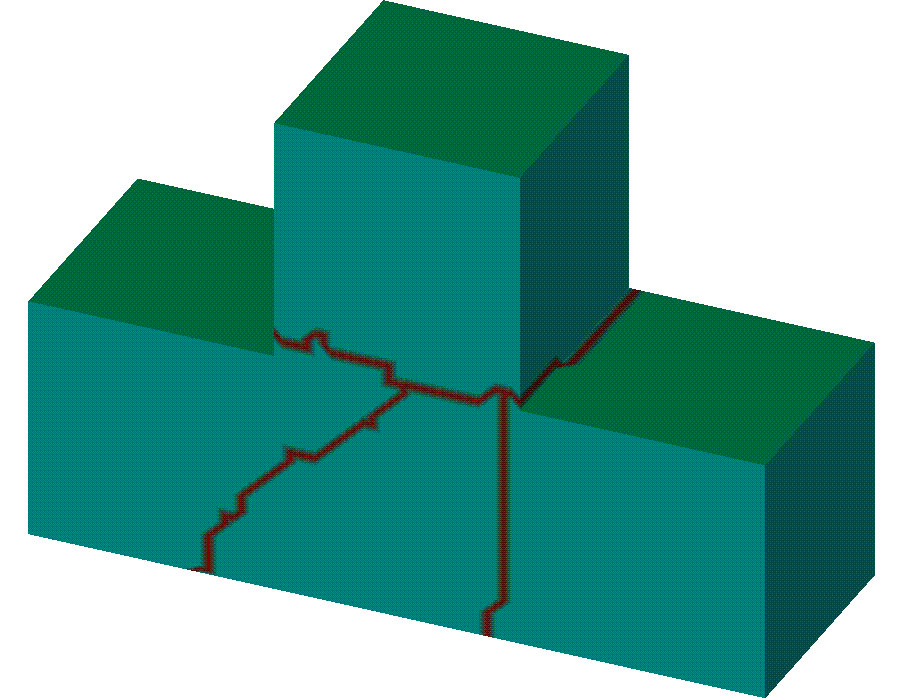

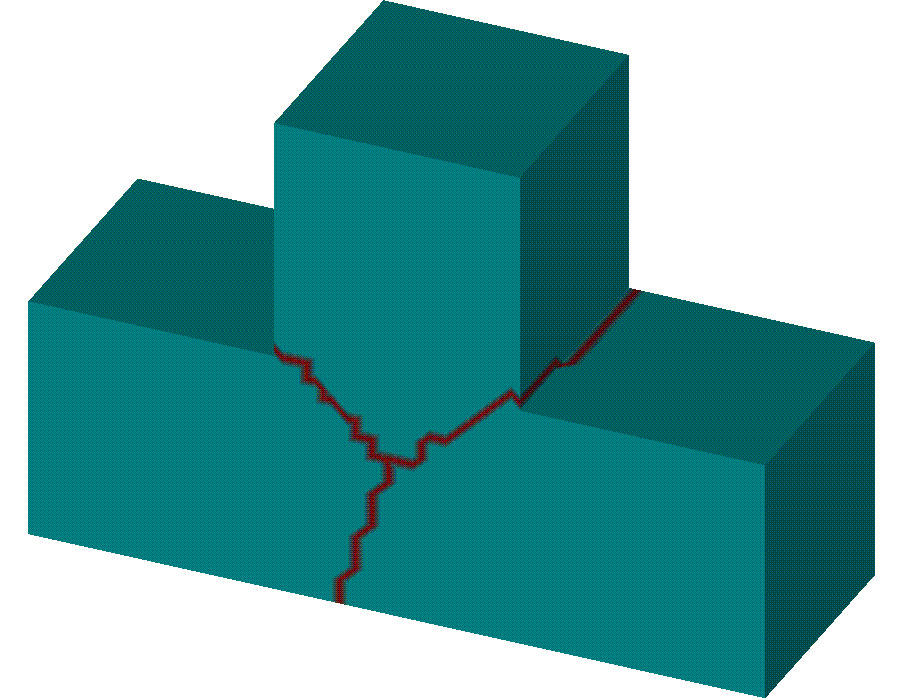

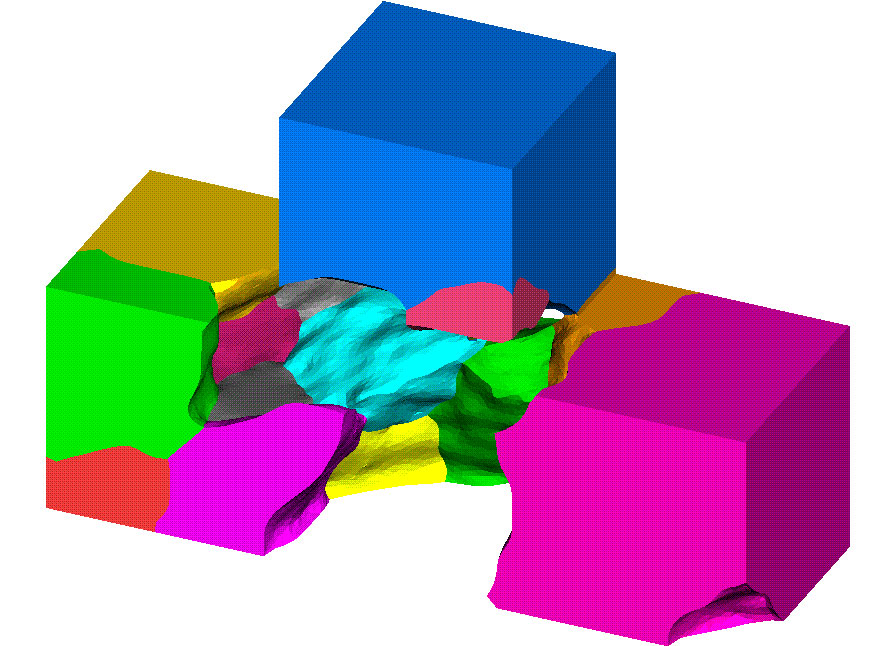

Laplacian smoothing can reduce the artificial roughness which is an artifact of the Potts model evolution. Here I show the same t=200 snapshot after Laplacian smoothing, using the “smooth” command I recently contributed to the LaGriT toolbox. This new command will be included in the next release (scheduled for October, 1998) of LaGriT, and is currently the only smooth capability in LaGriT which works on both the 2d surface meshes and the 3d volume mesh while preserving constrained interfaces, like the outer geometry of the “T” shown here. Laplacian smoothing does not however preserve volumes, but acts in some sense similar to mean-curvature motion in that it will shrink spheres if used iteratively. The version implemented is under-relaxed, and constrained not to invert the volumes of the tetrahedra of the mesh.

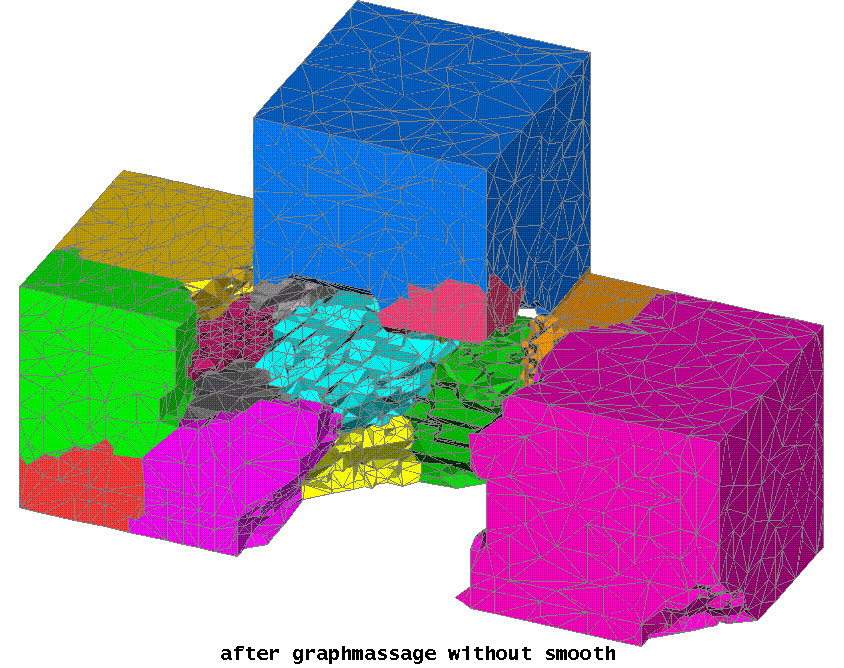

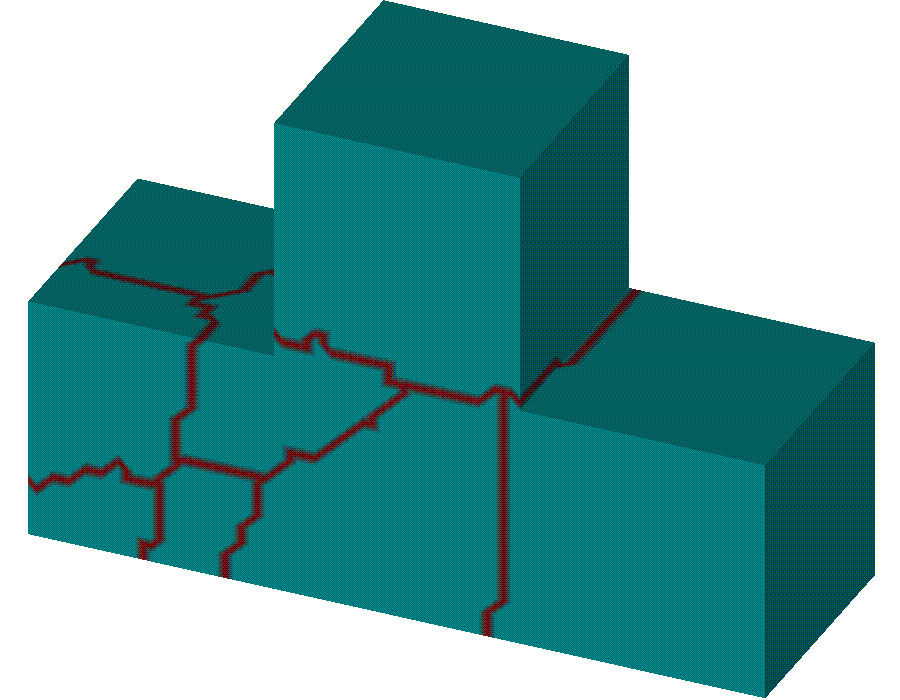

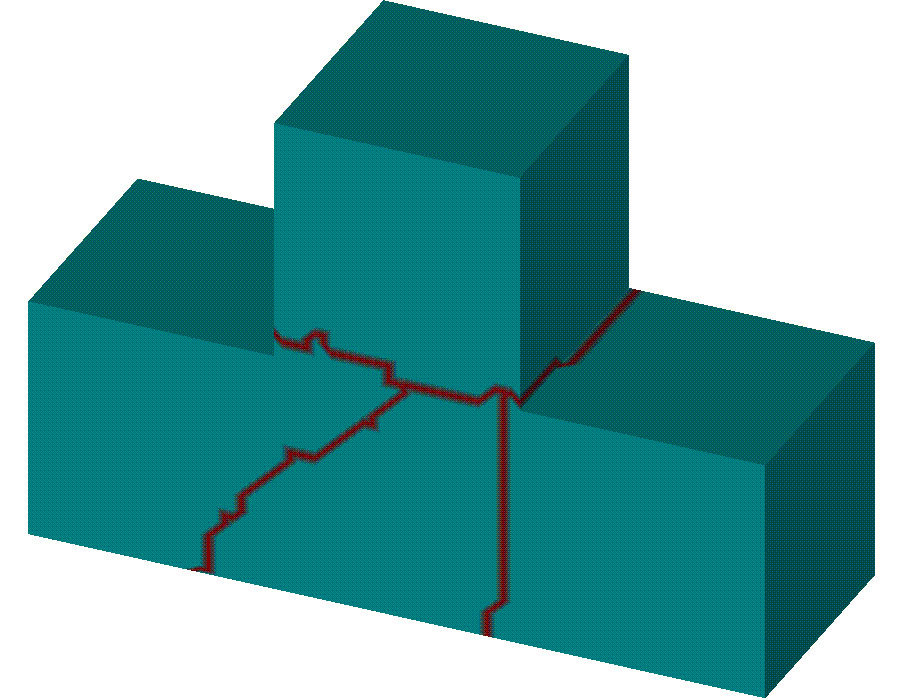

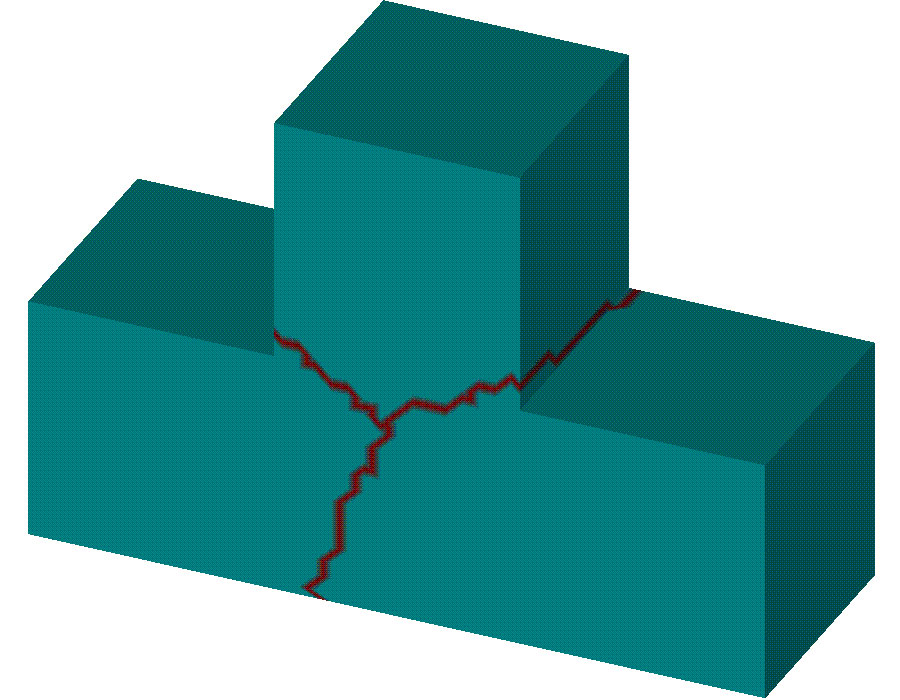

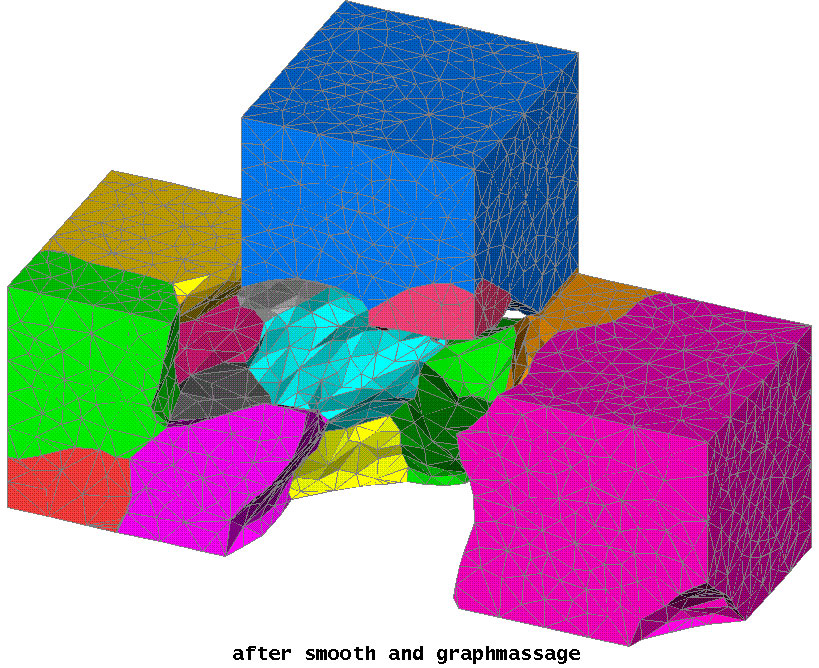

LaGriT’s “graphmassage” capability can then be used to reduce the node density and produce a good grid for further finite element computation. Here I show the same t=200 snapshot after massaging the smoothed grid, removing in this case 6 out of 7 nodes. The grid lines are also shown.

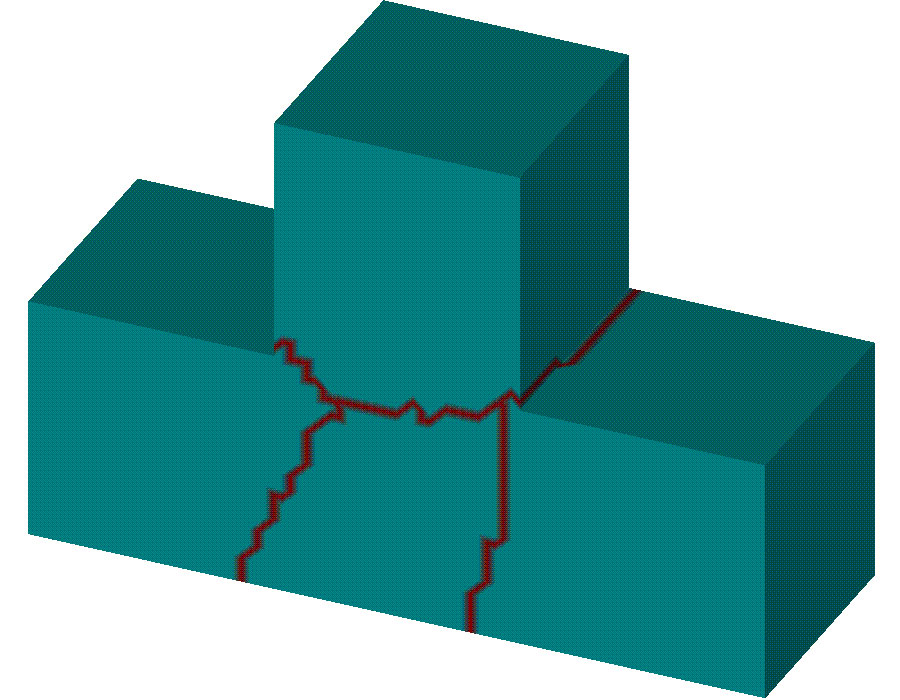

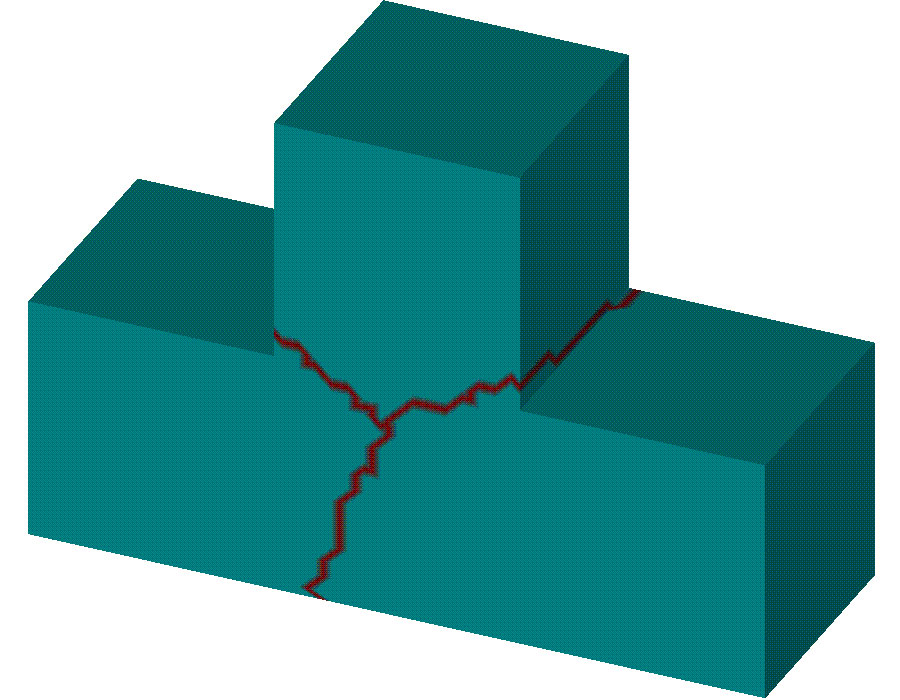

Using LaGriT’s “graphmassage” without first smoothing the structure does not yield as nice a grid, as “graphmassage” is not designed to smooth interfaces, but rather to preserve their character, as seen in the in the picture below resulting from “graphmassage” with the same parameters, but without the Laplacian smooth step. Smoothing after graphmassage also compares unfavorably to smoothing first, and then using graphmassage, as graphmassage with a small damage tolerance will not remove surface nodes on a rough interface, and with a large tolerance can introduce large-scale roughness.